“…I believe this is one of the most profound assessments of human-ecology dependencies that exist…” — Joel Salatin, in the ‘The Marvelous Pigness of Pigs”, referring to the Regrarians Platform®

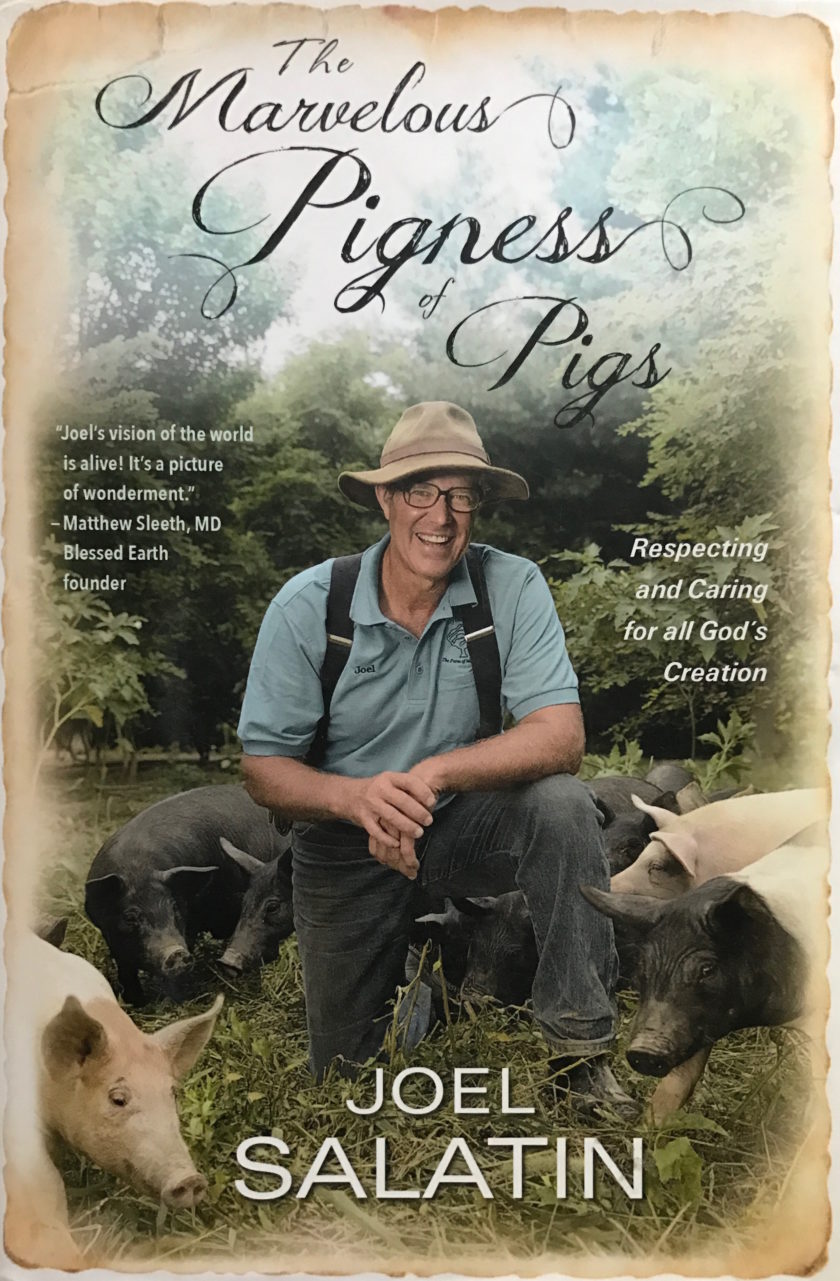

Polyface Farms’ Joel Salatin is widely regarded as one of the world’s greatest ever farmers. In the ‘regenerative agriculture’ movement there are perhaps no more influential people, with so many people using the farming principles that Joel and the 4 generations of Salatin’s (and their team!) apply at their farm in Swoope, Virginia, USA.

In 2016 Joel released his 10th book, “The Marvelous Pigness of Pigs – Respecting and Caring for all God’s Creation,” and in our opinion its one of his most important books yet. Of all of his titles this book reveals a spirit and biblical scholarship not found in his other books. He’s not a ‘bible-basher’ type and this book doesn’t have him show as being so — its a carefully crafted and direct challenge to not just Christians, but all people of faith and indeed all people without, to apply better attention to what needs to be taken care of as individuals, societally and as land stewards.

In the chapter ‘Dependence vs. Independence’ Joel outlines his interpretation of the Regrarians Platform® — one of the first we’ve seen in print.

Please find following an extract from pages 230-232 and please get this book!

“…The Australian water genius P.A. Yeomans developed what he called steps of permanence. That list has now been modified by another Aussie genius named Darren Doherty, who, with his wife, Lisa, founded Regrarians.

The idea is that these steps go from most permanent to least permanent. In other words, the hardest ones to change are the first ones, and the easier ones are the last ones. This list is both confining and liberating. Because it identifies boundaries, it keeps us from fretting and frittering away our time about things we cannot change. By the same token, it free us to work on the things we can. I believe this is one of the most profound assessments of human-ecology dependencies that exist. When we implement changes, they become part of the new environmental equity. Here are the ten “rules of the game” as Darren calls them:

1. Climate. It is what it is. I’d be foolish to bet my farm’s prosperity on growing bananas. I can’t change the rainfall, average temperature, longitude, or latitude. I’m dependent on that. However, I can do things to extend the season, like cold frames or greenhouses. We can modify, but only so much.

2. Geography. Darren calls this “the board game.” You aren’t going to turn your hills into flat ground or your marshes into high country. But you can create contour lines for keylining (invented by Yeomans — Water for Every Farm). Ponds for water catchment can be strategically placed.

3. Water. This the fuel that powers everything. Harnessing, storing, dispensing water are key. Plastic pipe lets you move water to places where current streams and springs don’t flow.

4. Access. Roads, pathways and lanes from ancient Roman times are still evident throughout Europe. Place these strategically for easy maintenance and to use as gutters to channel water to catchments.

5. Forestry. Trees change slowly, but we can accelerate change by pruning, strategic weeding, and other good silvicultural practices. How many and what kind of trees do you want long-term? Trees provide fuel, lumber, carbon, wildlife habitat, erosion control, hydrology cycling, transpiration. We depend on them.

6. Buildings. Portability is preferable because its the lowest cost and most versatile. Buildings will inevitably become obsolete. Realizing that our infrastructure is dependant on things beyond our control, like the economy, technology, or the interests of future owners, pushes us toward multi-use, simple, cheaper structures that can be easily modified.

7. Fencing. Ditto the buildings discussion above. One of my rules of thumb is this: install only what is obvious and necessary (like fencing out streams, ponds, gardens, access lanes). Leave everything else portable. Whatever you leave and don’t move for three years can be converted to permanent. On our farm all of our fences follow topographical lines. We have no straight fences; they’re all crooked to follow the terrain. Did somebody say something about being dependent?

8. Soils. Soil maps give a good starting point, but all soils can be upgraded with good management. Heavy soils or light soils dictate practices. Violating those rules has done and continues to do a lot of ecological damage.

9. Economy. The economy may go up and down and none of us can do anything about that, but the way we market, the way we interact with customers, ultimately dictates our success. So yes, we can’t change things on a macro scale, but we can greatly change our personal micro-economy.

10. Energy. We live in a petroleum-dependent time, and none of us can change the price of diesel fuel at our local stations. But we can move our farms to more solar-driven operations, whether that be actual solar panels or more leaves on plants to generate more biomass. We’ll see more development in this arena, of course.There you have it, the ten steps of permanence that our define our dependence on what is, but offer lots of opportunity for innovation within those confines. What a different discussion that the one engaged in by today’s industrial farmers. They live in a world of disease, commodity price roller coasters, sickness, stench, erosion, and economic fragility. To me, recognizing our dependence ultimately liberates us to responsible innovation…”